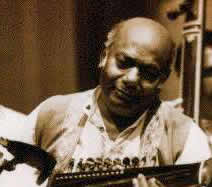

Music maestro Ali Akbar Khan reflects on his 85 years

Mumbai: Of the many thousands of concerts Indian master musician Ali Akbar Khan has performed, he particularly disliked a famous 1971 benefit show organized by Beatle George Harrison.

"That was not music but I`d say a war of music," said Khan, the world`s best-known maestro of the sarod, a fretless stringed instrument similar to the lute.

The Concert for Bangladesh brought together an all-star line-up including Eric Clapton, Bob Dylan and Ringo Starr, as well as Khan`s brother-in-law, Ravi Shankar, another prominent musician who was also a student of Khan`s famed father, Allauddin Khan.

With the concert`s rock music pounding at New York City`s Madison Square Garden, Khan stuffed his ears with toilet paper to block out the noise. "If you hear that music for one week, my ear will finish forever," he said.

Ahead of his 85th birthday on Saturday, Khan spent a few hours recalling the highlights of a rich musical career, his sometimes uneasy relationship with Shankar and a deep secret even his wife did not know. Recording since the 1940s, Khan played an important role in popularizing Indian music abroad.

Violinist Yehudi Menuhin, who played with both men, called Khan `an absolute genius, the greatest musician in the world.` Yet Khan shuns the showmanship - and lacked the patronage of Indophile Harrison - that helped make Shankar a superstar of the 1960s counterculture.

Shankar and Khan recorded several duet albums - and played together at the Concert for Bangladesh. But Shankar`s divorce from Khan`s musician sister and their separate career paths strained ties between the two titans of Indian music. Showmanship "is not important, the music is important," Khan said. "Our duty is to bring good feelings to others. It`s the best medicine for everyone, even trees, birds, animals."

Khan devoted much of his career to teaching the complicated ways of Indian music, following a long oral tradition. He set up the Ali Akbar College of Music in Calcutta in 1956 and moved it to the San Francisco area 40 years ago. "In India, the great musicians recognise me as the best," Khan said at his home in San Anselmo, a town north of San Francisco. "I don`t want to become famous. All that I wanted is to find some good students who want to learn music."

Very strict father: Suffering poor health in recent years - Khan needs four hours of kidney dialysis three times a week - he continues to teach vocal and instrumental classes, sometimes improvising as his disciples struggle to mimic his complex songs. "He`s sown a lot of seeds that have really implanted something about Indian music in the West," said Daisy Paradis, a sitar player who began two decades of study with Khan in 1966. "He`s definitely made a profound impact."

Some of the students at his college in San Rafael, near his home, have stayed with him for decades. Many rise as he approaches and departs, often touching his feet in a sign of respect to the guru.

Khan`s wife, Mary, estimates he has taught 10,000 students during his lifetime. Khan also attracted great Indian musicians to northern California; tabla wizard Zakir Hussein lives just three blocks from his house. "I`m proud that the people are really enjoying and also learning and playing and they are very happy," Khan said. He describes his own learning as far from happy under the demanding guidance of his father, a legendary Maharajah court musician from a long heritage of musicians, who listened for the smallest of errors and demanded endless hours of practice. "He was very strict. He never played with me, he never laughed, never smiled. He was a tiger," said Khan of a man who lived to be more than 100. "I wanted love from him."